An economic recovery is starting to solidify, but there are still issues that must be ironed out in regard to how monetary policy should react. For the better part of the past decade, the US has struggled to raise inflation to the Federal Reserve’s 2% target rate. Though this isn’t the first time this issue, which coincides with the decline of the Phillips Curve, has been acknowledged, Chairman Powell and the FOMC have finally decided to take action and re-assess how monetary policy will measure its effectiveness in the post-COVID era. A more dovish approach to management of inflation, which could begin to surge sooner than many expect, will be the prescribed cure for persistently weak price pressures.

As we head into the final quarter of 2020, quantitative easing remains business as usual at the Federal Reserve. One would be hard pressed to find dissenters to the bank’s continued buying activity amidst lingering uncertainty leftover from the COVID crash.

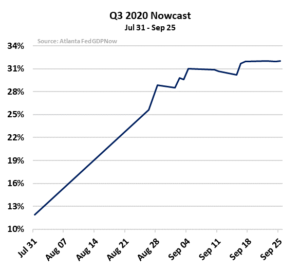

Thankfully, now more than 9 months after the start of this ongoing pandemic, one which upended almost any sense of normalcy in the world, an economic recovery is beginning to feel within reach. Green chutes are appearing across numerous datasets, especially those captured in the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model. In fact, as of September 25, the model projects third quarter GDP growth of 32% percent, due to strong auto and housing sales. That figure is almost 3x larger than their initial Q3 nowcast at the end of July.

Pending home sales rose 8.8% in August, reaching a record high pace, up by 24% YoY. The MNI Chicago Business Barometer, known more colloquially as the Chicago PMI, jumped to 62.4 in September of 2020 from 51.2 in August, a 2-year high, easily beating market forecasts of just 52.

Signals of a serious recovery are becoming increasingly visible, but those numbers have not come cheap.

Although the Fed’s balance sheet had begun to unwind a bit after the first wave of renewed QE, renewed growth in central bank assets have reinflated the size of the Fed’s balance sheet to more than $7 trillion.

Last year, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that federal debt as a share of GDP would come close to 80% in 2020. Now, the office sees that debt-to-GDP ratio at more than 98% by year end.

In addition, the expected budget deficit as a percentage of GDP has increased to 16% from just 4% last year.

Based on the latest CBO projections, the size of federal debt as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) will be 45 percentage points higher in 2049 than projections only a year ago…

To read the rest of this Viewpoint, START A FREE TRIAL You’ll also gain access to: If you already have a subscription, sign in